What would happen to global trade if the European Union (EU) implemented some form of carbon pricing for ocean shipping and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) did not follow suit, or did so years later, leading to a permanent or temporary ‘Balkanization’ of carbon-emission regimes?

On Dec. 2, the new president of the European Commission, Usula von der Leyen, affirmed during a speech at the United Nations climate conference (COP25), “Ten days from now, the European Commission will present the European Green Deal.” She said that in March 2020, “we will propose the first-ever European Climate Law, [which] … will include extending emission trading to all relevant sectors … [including] transport.”

The possibility of unilateral carbon pricing was cited in the International Monetary Fund working paper, “Carbon Taxation for International Maritime Fuels: Assessing the Options,” published in September 2018. That paper pointed out that “the European Parliament has declared its intention to proceed with regional carbon pricing in the absence of a global agreement.”

On one hand, recent developments in the EU, the perennial sluggishness of IMO progress and the inherent hurdles to global consensus suggest that a “EU now, IMO later” scenario is conceivable.

On the other hand, that would only be possible if EU member states unanimously agreed — which is an enormous “if.”

Challenges to a global solution

The difficulty in obtaining global approval of a carbon tax or some other carbon-pricing system for marine emissions was highlighted by recent events at the IMO. During of the IMO’s Intersessional Working Group on Reduction of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions from Ships that concluded on Nov. 15, a proposal to limit ship speed to reduce carbon emissions was set aside in favor of target-based measures.

Numerous shipowners backed the slow-steaming proposal. That’s not surprising. Speed limits would significantly reduce their fleets’ GHG emissions while virtually guaranteeing that the cost of those reductions would be paid by charterers and cargo shippers. Slower speed reduces effective vessel supply and increases freight rates.

Prior to the IMO working group meeting, Ridgebury Tankers CEO Bob Burke predicted the negative outcome of the slow-steaming proposal while speaking on a panel at the Marine Money conference in New York on Nov. 13.

“Speed limits would cost the charterers money, meaning there will be a lot of pushback from them — I doubt there will be any traction, ” he said.

“When OPA ’90 [the law stemming from the Exxon Valdez spill] was being discussed, hydrostatic loading would have solved the problem immediately [versus the chosen transition to double hulls].” In hydrostatic loading, the cargo level is limited to assure that if the tank is breached, seawater flows in and oil doesn’t flow out. “That was categorically rejected by the oil companies because it would cost them money,” noted Burke.

That same pushback seems plausible if a global carbon pricing system is pursued. The IMF paper made the case for an international carbon tax. During the meeting of the Global Maritime Forum in late October, BW Group chairman Andreas Sohmen-Pao said, “To meet international shipping’s decarbonization challenge, the maritime industry needs a carbon levy. It is coming and we should shape it.”

During the Marine Money forum, DryShips CEO George Economou was asked about the prospects for a global carbon tax on shipping. He replied, “The problem is we can talk about it, but it’s the oil companies that will take the decision.

“Can you imagine if the oil companies said they would put aside 30% of their profit to develop something new [i.e., fund the development of low-carbon-emitting shipping solutions]? If you were an investor in an oil company would you like that? No. So I think they will resist it, and it’s not going to happen anytime soon.”

It is not just the oil companies. Most of the world’s largest corporate entities depend upon the cheap movement of goods across the oceans. In some cases, these entities are state-owned.

A country’s leadership could balk at implementing carbon levies on shipping if the added price jeopardized its imports, exports and economic growth. That creates a high hurdle to global consensus.

Challenges to a regional solution

The challenges to a non-global solution, such as an EU-only carbon-pricing system, were addressed in the World Bank working paper, “Regional Carbon Pricing for International Transport,” published in January 2018.

That paper noted that a regional levy would have to be implemented by the port state (not a flag state, i.e., the ship register) and would have to incorporate GHG emissions beyond the port state’s territorial waters. “The scope of port-state jurisdiction with regard to activities that take place beyond the state’s territorial waters is a debated issue,” said the paper.

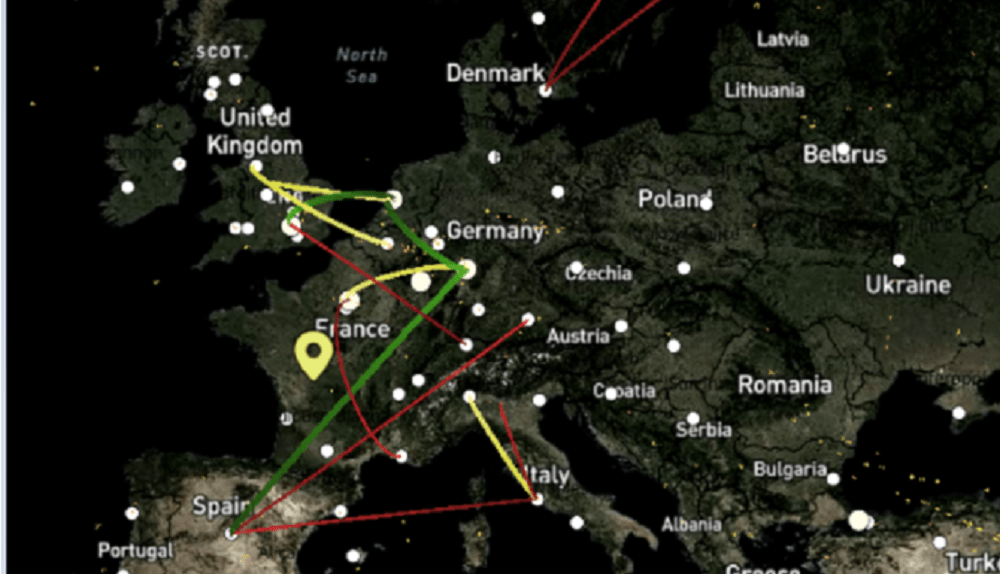

Assuming the EU or any other regional body could win the legal jurisdictional argument, the next challenge is preventing shipping interests from gaming the system. If the carbon pricing applies to the time at sea between the arrival of the cargo and its departure from the previous port, shippers could increase the use of transshipment at a nearby hub to minimize the transport covered by the carbon pricing.

Another complication arises with exports of petroleum products and liquefied gas. Such cargoes are often traded multiple times while in transit. The final destination is often not known when the ship departs. If the EU had a carbon-pricing system, how would it determine the pricing for such a destination-flexible cargo, or prevent that cargo from being “sold” to an entity in a nearby port and then ultimately resold farther afield?

What the World Bank working paper does not address is the even greater obstacle to regional carbon pricing arising from basic shipping-market dynamics. If costs are passed along to cargo shippers, it would impact the price of EU imports and the competitiveness of EU exports versus other regions. If costs are borne by vessel interests, those vessel interests — which can sail anywhere in the world — would have less incentive to serve EU ports, meaning that costs would still ultimately be borne by EU importers and exporters due to scarcer vessel supply.

Political challenges to an EU-only solution

The whole question of whether an EU carbon regime for shipping could exist in the absence of a global regime may be based on the flawed premise. According to Pablo Rodas-Martini, senior associate of SQ Consult, a Dutch company specializing in climate change and carbon markets, “The possibility of a carbon tax imposed by the European Commission is very low — it’s almost impossible.”

Rodas-Martini told FreightWaves, “The reason is straightforward: According to the regulations of the EU, any new tax must be agreed by unanimity by all member states. Such a requirement makes it almost impossible to think that a carbon tax will be proposed for the shipping sector.

“The approval of the energy tax took about 12 years due to this requirement. In the leaked text on the green deal, it is mentioned that the new commission wants to ‘pursue efforts’ to scrap this unanimity rule but, well, we are still very far from that point.

“More than a carbon tax to the shipping industry, the European Commission and the European Parliament have mentioned in the past that shipping should also be included in the European Union Emission Trading System [EU ETS], in a similar way as the aviation sector was added a few years ago,” he continued.

“That EU ETS includes power plants and energy-intensive industries across the EU. However, in the case of aviation, only the intra-European flights have been added to the EU ETS. If shipping is added, it would be under similar conditions: only the intra-European cargo, which would leave most of the shipping operations outside the EU ETS, since in the case of shipping, the intra-European share is much lower than the intra-European share for the aviation sector.

“This issue — the relatively small share of intra-European cargo for shipping — will force the EU to put more pressure on the IMO, [to push the] IMO to implement a much more ambitious climate change strategy,” he concluded.

Proactive shipping industry efforts

To date, confusion over the IMO’s future course on carbon emissions has actually been a positive for shipowners’ profit prospects. Uncertainty has spurred fears about the obsolescence risk of newbuildings. This concern has drastically reduced new ship contracting, which limits future vessel supply and supports freight rates.

The industry is well aware that carbon-related consequences could turn negative. As a result, it is seeking to proactively address the issue through the Global Maritime Forum and via voluntary industry initiatives such as Getting to Zero Coalition and, on the ship-finance front, the Poseidon Principles.

As Eagle Bulk (NASDAQ: EGLE) CEO Gary Vogel explained at the Marine Money forum, “If you look back at ballast-water treatment and to some extent IMO 2020, we’ve hopefully learned that it’s very important to have a seat at the table. Particularly with ballast-water treatment, with all the misinformation and the starts and stops – that’s not helpful.

“If you look at decarbonization and how much bigger that is for the industry, whether it involves a carbon tax or other means, we know that we have to have a better outcome [than occurred with previous regulatory initiatives]. It’s about being there, having a voice at the table and making sure that we are on a better trajectory, because this is too big of an issue to bolt the wings on while we’re in mid-flight.” More FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller