The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of FreightWaves or its affiliates.

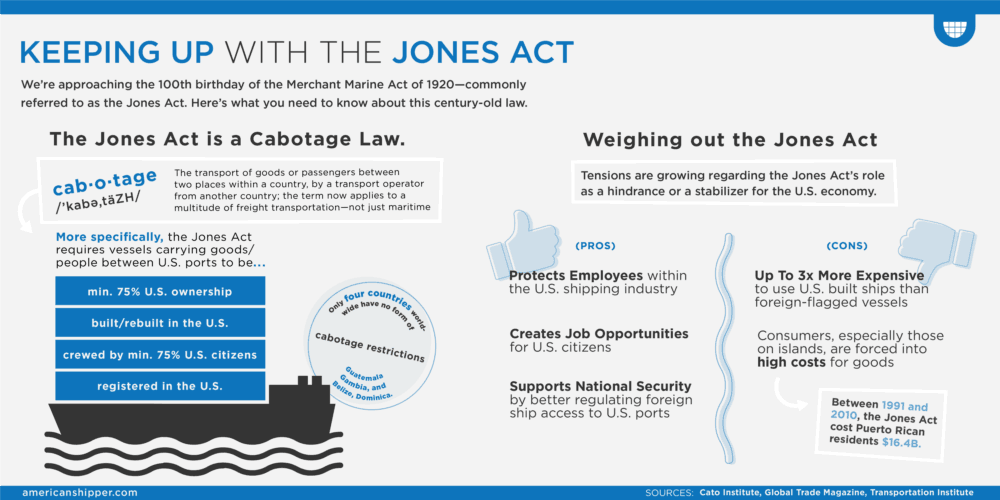

The Merchant Marine Act (1920) outlines one of the most consequential non-tariff barriers (NTBs) in U.S. history, and June 5th will mark its 100th anniversary. Often called the Jones Act after its sponsor, Sen. Wesley L. Jones (R-WA), the intent was to incentivize the building and maintenance of a domestic fleet of commercial ocean vessels that would be owned and operated primarily by U.S. citizens. The Jones Act set this requirement to ensure both national defense and a “proper growth of commerce” using the “best type of ships.” Regulators have since interpreted this to mean that the vessels must also be built by U.S.-owned shipyards. Most countries have some form of cabotage restrictions but the U.S. stands out with its domestic build and repair requirements in the maritime sector.

Cabotage is defined by Merriam-Webster as the “trade or transport in coastal waters or airspace or between two points within a country.” The Jones Act covers not only coastal commerce but the commerce of U.S. territories and possessions. As such, port-to-port transport of freight from the contiguous U.S. to Alaska, Guam, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, etc. can only be handled by U.S.-flagged vessels (meaning U.S.-built, U.S.-owned and U.S.-crewed). Section 27 of the act includes the same prohibitions on transport by land as well as by water. Of course, as the commercial air industry grew after World War II cabotage restrictions were applied there as well. In practice cabotage restrictions of some kind apply to all point-to-point domestic transport of passengers and/or freight regardless of mode.

Why the Jones Act was enacted

The Jones Act was certainly a creature of its times and it made some economic and political sense. Economically, the U.S. emerged from World War I with a need to expand its commercial fleet while protecting its growing domestic commerce from foreign vessels. Supporting U.S. shipbuilding capabilities to meet the expectations of the Jones Act is a classic example of the “infant industry argument” in support of trade protection. Politically, U.S. coastal states with large shipbuilding interests would benefit from the act’s restrictions on cabotage. Sen. Jones himself no doubt benefitted from giving his constituents in Washington State a near monopoly on shipping to and from Alaska. Of course, the problem with infant industries is knowing when to wean them off of the mother’s milk of trade protection so that they can try to survive and thrive in the cold world of international competition. Avoiding this simply incentivizes an industry to remain cost-heavy and uncompetitive.

As an NTB the Jones Act has its supporters as well as its detractors. Supporters laud its spirit of national defense. This means that in time of war or emergency any vessel and crew operating along U.S. coasts and rivers would be “American” and thus not of questionable loyalties if commandeered to move military equipment and/or personnel. Detractors see the Jones Act as antiquated and serving only to keep transport costs higher than they would be otherwise. This is due, the argument goes, to the stifling of foreign carrier competition in domestic freight markets and propping up U.S. shipyards with their lower economies of scale and higher labor costs than those in Asia. This is the classic conflict between free trade versus ensuring stable domestic industries and employment.

Today the Jones Act enjoys bipartisan support in Congress and it is hard to imagine President Trump setting aside his mercantilist tendencies to support any large-scale reform. Yet the Jones Act has enough wrinkles, loopholes and exceptions to keep politicians, regulators, transportation lawyers and even professors of logistics on their toes.

Political pressure for cabotage reform does arise from time to time. The latest was at the G7 Summit in August 2019 when U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson encouraged President Trump to consider supporting U.K. vessels wishing to engage in U.S. cabotage. Currently, EU nations can engage in multimodal cabotage among themselves. It would be interesting to see if a post-Brexit U.K. could maintain its cabotage rights with EU nations and, at the same time, successfully build such rights into a bilateral trade agreement with the U.S. However, it should be remembered that U.S. cabotage options with neighboring Canada and Mexico are very limited – despite each being a much larger merchandise trade partner than the U.K.

Some Jones Act wrinkles

The U.S. build and repair requirements apply only to domestic water vessels. U.S. airlines can buy airplanes from Airbus, Bombardier and Embraer, etc. U.S. motor carriers can buy Volvo trucks (or Mack trucks, which has been a Volvo subsidiary since 2000). Municipal governments offering light rail transit and bus services can buy their conveyances from Siemens and New Flyer, respectively.

Of course exceptions to the rule barring foreign companies from offering domestic transport can occur in times of emergency or when a domestic vessel is not available for the required move. These assessments are made by the Executive Branch or by Congress. Notable emergency exceptions to the Jones Act were made for foreign vessels to assist with the clean-up of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 and relief after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Regarding domestic vessel availability, Alaska has the dubious distinction to have played a part in the largest Jones Act fine in U.S. history. In 2011, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) fined Furie Operating Alaska (then known as Escopeta Oil & Gas) $15 million for using a Chinese-flagged heavy-lift vessel to haul a jack-up drilling rig from the Gulf of Mexico to Alaska’s Cook Inlet. In 2017 both parties negotiated a settlement and the payment was reduced to $10 million. Ironically, Escopeta was granted a Jones Act waiver in 2006 to use a foreign vessel for the haul. But the haul did not proceed until March 2011 and by then the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) declined to renew the waiver. At any rate the haul proceeded from the Gulf of Mexico, around South America, and up to Vancouver, British Columbia, where U.S.-flagged tugboats took over and completed the trip in July 2011. Escopeta claimed that its tight timeline to reach Alaska before its tax breaks on drilling expired had forced it to use the foreign-flagged vessel. DHS did not agree and the fine was assessed by DOJ. Fast forward to 2019 – citing production difficulties in Alaska and unpaid debts, Furie filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in August of that year.

Special air cargo circumstances in Alaska

Alaska has a more positive cabotage story regarding foreign air cargo. Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport (ANC) is centrally located at 9.5 hours flying time to 90% of the industrialized world. This makes it an excellent air cargo trans-shipping point. This operational advantage is accentuated by an exception to the Jones Act. ANC’s innovative air cargo transfer program allows belly-to-belly transfer of U.S. bound cargo between a foreign air carrier’s aircraft or between those of two different foreign air carriers. This would be illegal at any other airport in the contiguous U.S. Furthermore, when the foreign airplane continued to another U.S. airport it would constitute cabotage. Why is this allowed at ANC?

Basically, Alaskans can thank the advocacy of the late Sen. Ted Stevens, when he wrote this unique operation into a re-appropriation bill for the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) back in the mid-1990s. Regulators now consider foreign air cargo landed at ANC and destined for the contiguous U.S. to still be “international” and therefore not a cabotage move in the spirit of the Jones Act. Despite this liberalization, ANC’s management team has had to work hard to convince skeptical Asia-based carriers that this quasi-cabotage activity is quite legal. What makes it hard to believe at first is why the U.S. would offer such a unilateral trade benefit to countries like China and Japan.

Transit by ship and tour buses

Now consider tourism. Many cruise ship passengers embark on their trips to Alaska from the Port of Seattle. They will cruise up the West Coast and dock at various Alaska ports. Interestingly, these foreign cruise ship companies rarely use U.S.-flagged vessels. But how is it not cabotage if the passengers are steaming from one U.S. port to another by foreign-flagged vessels? Certainly, most of Alaska’s ocean freight is delivered from the Port of Tacoma (Washington) by TOTE Maritime and Matson, which by law must use U.S.-flagged vessels. Why the difference?

Such Alaska cruises may be a cabotage move by definition but it is actually a type of cabotage move not covered by the Jones Act. Cruise ship and ferry activities in the U.S. fall under the Passenger Vessel Services Act (PVSA; 1886). As long as the domestic trip is “broken” by a visit to a foreign port along the way the cruise would be legal under the PVSA. Besides, passengers usually do not complain if their trips to Alaska are topped-up by a stop at the Port of Vancouver or Port of Victoria, British Columbia. On the other hand things might seem odd when a cruise from San Diego to Hawaii is interrupted by a quick stop at the Port of Ensenada in Baja, Mexico. Yet this move is necessary for the foreign-flagged vessel to comply with the PVSA.

Canada- and Mexico-based tour bus companies certainly do not fall under the PVSA but they do enjoy a similar protection. Foreign tour buses can pick up passengers in the U.S. and take them on a roundtrip tour of Canada or Mexico, as the case may be. The key requirements are that most of the tour takes place in a foreign country (i.e., it is international commerce) and the passengers are returned to their U.S. point of origin. Picking up and dropping off passengers at different U.S. points along either leg of the tour, however, would constitute illegal cabotage.

Motor carriers and freight

The U.S. motor carrier sector is particularly tricky since a Canada- or Mexico-based conveyance is covered under customs laws, while their drivers are covered under separate immigration laws. These laws and regulatory interpretations do not conform to one another. For example, U.S. customs regulations allow for very limited options for foreign motor carriers to engage in cabotage. The move must be “incidental” to a well-defined export or import move. Another option is to carry cabotage freight while “repositioning” between well-defined export or import moves. Typically, the cabotage move must be “outward” – meaning, for example, that the conveyance is traveling northward from the U.S. back to Canada. Canada, on the other hand, allows repositioning moves to be east-west and this creates confusion in the trans-border motor carrier sector. Simply put, different countries can have different laws and regulatory interpretations. Of course, the moves noted above apply only to conveyances. U.S. immigration regulations are not as liberal – which means, in practice, these cabotage moves are often rendered impractical.

Foreign drivers would, however, be able to undertake incidental or repositioning moves if they were dual citizens, held a Green Card or were at least 50% by-blood members of a First Nation tribe in Canada. Canada extends the same courtesy to similar persons from U.S. tribes. This derives from the Jay Treaty (1794). The quick history is that the United States and British North America, while drawing their common border, did not want to zig-zag it around tribal lands. Today, for all intents and purposes a U.S. or Canadian native with an appropriate Band (tribal) Card is treated like a dual U.S.-Canadian citizen. Trans-border motor carriers doing business in the U.S. and Canada might find it revenue-enhancing to hire such people for their fleets or use them as owner-operators.

In 2020, does the Jones Act necessarily add to U.S. national security or is it just a jobs program? If this is an example of the infant industry argument, the baby is turning 100 years old this year. Economics and politics always make for strange bedfellows.